Welcome back to the “Antarctica Episodes” here on GreenerGrass.com. In our last episode, we covered The Wildlife. This time, we’re talking about the role humans have played throughout Antarctica’s history. Here goes…

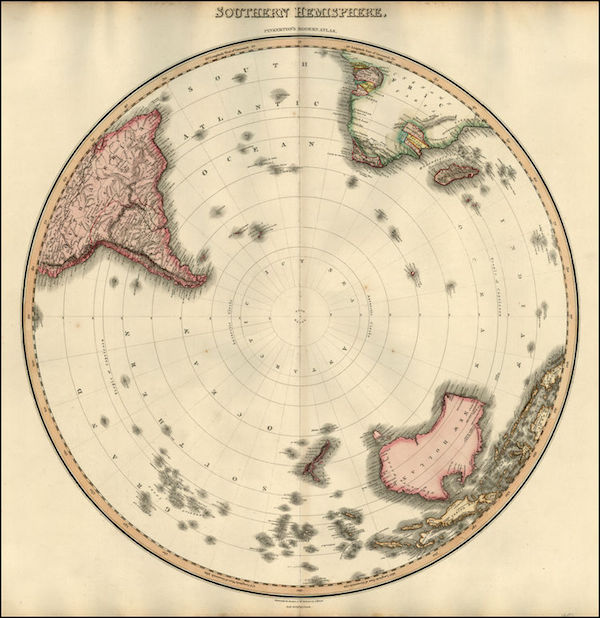

For most of human history, Antarctica lay undiscovered in the Southern Hemisphere protected by bad winds and cold temperatures.

- In 1773, Captain James Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle (66 degrees South – we only made it to 65 degrees south).

- In 1775, he found the South Sandwich Islands.

- In 1819, Englishman William Smith found the South Shetland Islands (where my journey began).

- Finally, in 1821, a sealer from the United States, John Davis, was — likely — the first person to set foot on the Continent.

Waterboats were used by whalers to gather ice. They’d fill the boats with ice, melt it, and use the water to process whales.

Antarctic history can be quite controversial. Like most great moments of exploration, there was a commercial reason to explore the Continent. At the end of the 19th and early in the 20th Centuries, it was for whales. Their blubber lit most of Europe and the States. As a result of such high demand, whalers had depleted supplies in many of the easy-to-get-to oceans, so they headed farther and farther south. This resulted in bustling “cities” like Whaler’s Bay on Deception Island. At its peak, there were 200 people living there supporting the many whalers. Today, the cemetery and some of the structures remain. Most existing manmade structures in Antarctica are covered by the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, which prevents their destruction or removal. In other words, they’re simply decaying back into the earth.

These fuel storage tanks remain on Deception Island. Thanks to the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, many man-made structures must remain in place and untouched.

To put it mildly, whaling was a pretty grim proposition. At one of our evening lectures, the ship’s historian presented a graphic speech about the disgusting nature of whaling. It involved lots of blood, guts, and strong odors. Discarded whale carcasses were strewn everywhere. He shared the story of one New Year’s Eve celebration when the whalers learned dead whales are not good bases for launching fireworks. In short, he spared no details describing what it was like to live on a whaling station. It was utterly fascinating. And, unlike many of the other lectures, even my new friends — Mike, Donny, and Aaron — seemed to be enjoying this one.

Suddenly, there was a rustle at the back of the room. Then more noise. And more. Finally, we all turned around.

There was a group of people with us who had come to Antarctica in order to meditate (we cleverly called them the “Meditators”). And, in response to this lecture, the Meditators were standing up. And — one by one — walking out. Apparently, they didn’t want to hear how whales got ripped apart. I think they really liked whales. In fact, they told one staff member that they’d all meditated on the issue of her next life and they now believed she’d come back as a whale. She asked me if I thought that was a fat joke. I declined to answer.

This hanger was part of the effort to bring flying to Antarctica. It’s still unusual for a day that’s calm enough for flight. The first flight to the Continent landed here at Deception Island in 1928.

The Great Meditator’s Walk Out as it came to be known was quite a topic of intrigue among the other passengers. Without access to the outside world, you don’t talk about who’s ahead in the polls or what’s up with the latest Hollywood marriages. Instead, you address issues like whether the Meditators should have walked out. Of those with an opinion (which excluded me), the ship was pretty evenly split on the controversy. One guy (pro-walk out) told me at lunch that I owed the whales a debt.

He said, “I’m still atoning for the sins of our forefathers. As I gaze into the eyes of those majestic creatures, I just want to say I’m sorry. You should too.”

I chose not to ask the guy to explain how he looked into a whale’s eyes.

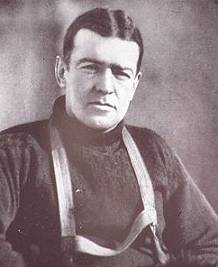

Shackleton and The Endurance

Antarctic history isn’t all about whaling, though. One of my favorite tales is the story of Sir Ernest Shackleton. After leading two wildly successful Antarctic expeditions, he was a tremendous worldwide celebrity. Kind of like the Justin Beiber of his day, but with purpose.

Now, he was ready for the big step: He planned to be the first man to reach the South Pole. Unfortunately, he was beaten by the Norwegian Roald Amundsen who, in 1911, found it first. Shackleton was pretty mad. He missed his moment. But, lucky for Britain, he was the ultimate one-upper. He opted for a cross-continent stroll. That’s right!

He thought to himself, “what kind of loser walks to the South Pole and turns around? Not me. I’m going down there and we’ll keep on walking until we get to the other side of the continent. Boom!”

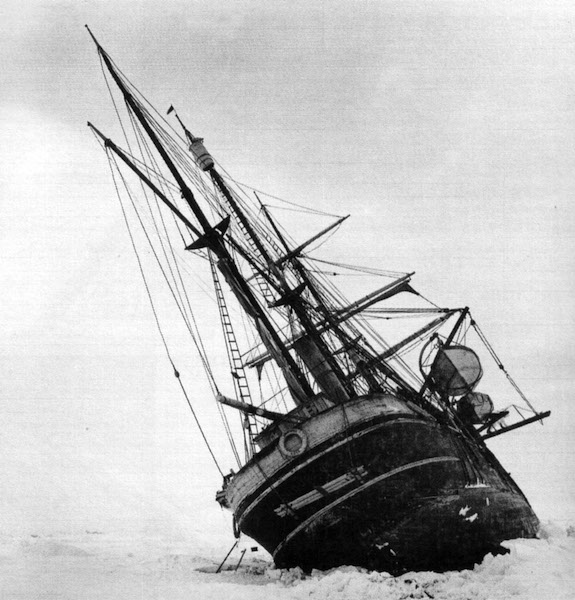

It turned out not to be quite that simple. The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914 started out rough.

Before they even set foot on the continent, Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, got stuck in ice that was up to 30 feet thick in the Weddell Sea. It was 1914 so he couldn’t really pull out his cell phone. (Heck it’s 2016 and I can’t pull out my cell phone and ask for help!)

So, Shackleton and the crew waited on the ice in hopes that the ship would break free. It didn’t. Instead, it got crushed. By that point, they’d been on the ice for almost 500 days! They finally launched the lifeboats and sailed to Elephant Island and ultimately on to South Georgia (that’s 720 nautical miles in open boats…in Antarctica!!). Only three men died. They spent almost two years living on a diet of penguins and seals, battling temperatures well below zero. And they didn’t have North Face jackets or comfortable boots. These were real men.

One evening, one of the ship’s historians presented a fascinating lecture on the topic of surviving an Antarctic Winter. It was less controversial than whaling and it was pretty easy to listen with our full bellies and warm chairs. In fact, based on the number of people snoring, I’d say we were almost too comfortable.

In our next episode, we’ll be exploring the science in Antarctica. Stay tuned!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks